Hours after India and Taliban-ruled Afghanistan held their first high-level meeting, the Taliban announced that they had urged Delhi to issue visas to Afghan businessmen, patients and students.

Hafiz Zia Ahmad, deputy spokesperson for the Afghanistan Foreign Ministry, in a series of posts on X, said the request for issue of visas was conveyed by acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi to Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri when they met in Dubai Wednesday.

The issue of granting visas is complicated and a hard ask for mainly three reasons: the Indian government does not officially recognise the Taliban government; the Indian security and intelligence establishment has flagged security threat perceptions regarding visa seekers from Afghanistan; and the Indian government does not have a functional visa section at the Indian embassy in Kabul or functional consulates in Afghanistan.

To assuage Indian security concerns, Muttaqi and the Taliban delegation, sources said, assured the Indian side that there would be no threat from those who would travel to India. The Taliban said they would ensure the vetting of those being granted visas.

But this is a very tricky issue for the Indian government since it has been very strict in issuing visas to Afghans after the Taliban takeover of the country in August 2021.

Following the capture of Kabul by the Taliban and the collapse of the Ashraf Ghani-led Afghan government on August 15 that year, the Indian government decided, four days later, to cancel all physical visas issued earlier to Afghan nationals, who were yet to arrive in India.

Afghan nationals who had physical visas on their passports were no longer able to travel to India. All airlines concerned were notified about this decision with instructions not to allow Afghan nationals holding physical Indian visas to board India-bound flights.

The Indian government introduced a new category of ‘e-Emergency X-Misc’ visa for Afghans who wished to travel to India. So, those Afghan nationals were advised to apply for an Indian visa on the e-Visa portal.

Only those Afghan nationals who had the Electronic Travel Authorization (ETA) for e-Emergency X-Misc visa issued by the Bureau of Immigration – it comes under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Home Affairs – were allowed to board India-bound flights.

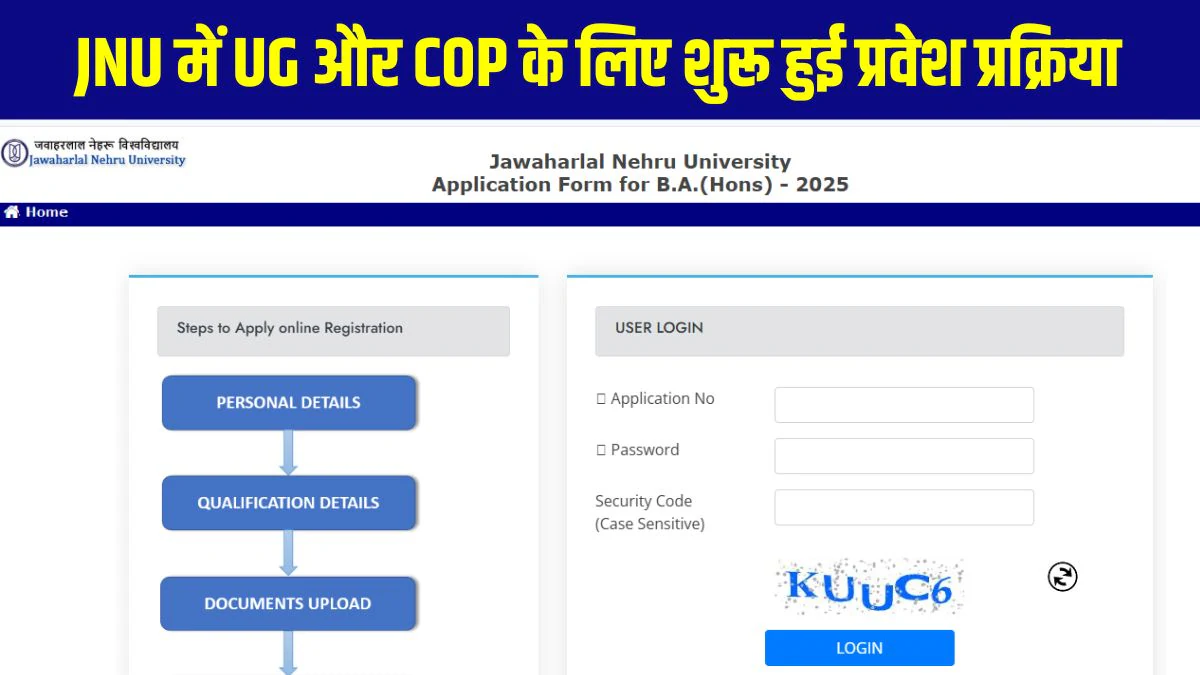

Scores of students, who wanted to pursue and continue higher education in India, were stuck and stranded at home, but the Indian government, at that time, took the call of not granting visas.

Within the Indian establishment, security agencies had red-flagged this issue and had outvoted the Ministry of External Affairs and Education who were keen to support this need of Afghan students.

The MEA, in coordination with the Education ministry and higher education bodies and universities where Afghan students were already enrolled, had asked universities to roll out online courses and classes for Afghan students in Afghanistan and overseas.

The Indian establishment was somewhat considerate in allowing some Afghans who wanted to come to India for medical treatment, but the numbers were nowhere near that before August 2021.

Some Afghan businessmen, who had been doing business for years and decades, especially of dry fruits, were coming to India regularly. That was a steady but a small number.

Now, the Taliban, facing difficulties in managing their healthcare system, are keen that Afghans be allowed to come to India for medical treatment. More so, after the Pakistan government has become so hostile to Afghans.

According to Hafiz Zia Ahmad, the “two sides agreed to facilitate visa and trade” when they met in Dubai.

The Indian government’s statement on the meeting did not mention this. It only said Foreign Secretary Misri “conveyed India’s readiness to respond to the urgent developmental needs of the Afghan people”.

Sources said Muttaqi had come prepared for the meeting in Dubai, accompanied by officials from the ministries of Commerce and Transport, and that reflected their intent.

Sources said the Taliban are aware of the Indian hesitation in granting official legitimacy to their regime, but want to move forward on “pragmatic” and “workable” solutions to their problems and challenges.

The Indian side, however, has to take a call based on the security dimension of the decision, as well as the political impact of such decisions. As visa issuance requires large manpower capacity in the embassy, and reopening of the Indian consulates, this would also be a political and diplomatic call.

Currently, the Indian embassy in Kabul is run by a small technical team which manages the delivery of humanitarian assistance and maintains contacts with the Taliban regime. Running visa services would require more manpower – officials and staff – at the embassy. This scaling would signal a higher diplomatic strength and presence on ground, which could tantamount to political signalling of upgrading the Indian diplomatic presence.

Stay informed with access to our award-winning journalism.

Avoid misinformation with trusted, accurate reporting.

Make smarter decisions with insights that matter.